By David Nickum For more than a decade, the battle over Colorado’s Roan Plateau—a beautiful green oasis surrounded by oil and gas development—raged in meetings and in courtrooms. At issue: Would the “drill, baby, drill” approach to public lands carry the day and the path of unrestrained energy development run over one of Colorado’s most valuable wildlife areas? Or would “lock it up” advocates preclude all development of the Roan’s major natural gas reserves?

Luckily, this story has a happy ending—and a lesson for Colorado and other states in the West struggling with how to balance the need for energy development with conservation of public lands and irreplaceable natural resources.

The Bureau of Land Management recently issued its final plan for the Roan Plateau, closing the most valuable habitat on top of the plateau to oil and gas leases. The plan, which will guide management of the area for the next 20 years, also acknowledges the importance of wildlife habitat corridors connecting to winter range at the base of the Plateau.

At the same time, the BLM management plan allows responsible development to proceed in less-sensitive areas of the plateau that harbor promising natural gas reserves and can help meet our domestic energy needs.

What happened? After years of acrimony and lawsuits, stakeholders on all side of the issue sat down and hammered out a balanced solution. Everyone won.

It’s too bad it took lawsuits and years of impasse to get all sides to do what they could have done early on: Listen to each other. We all could have saved a lot of time, money and tears.

The Roan example is a lesson to remember, as the incoming administration looks at how to tackle the issue of energy development on public lands.

There’s a better way, and it’s working in Colorado.

The BLM also this month, incorporating stakeholder input, closed oil and gas leasing in several critical habitat areas in the Thompson Divide—another Colorado last best place—while permitting leasing to go ahead in adjacent areas.

That plan also represents an acknowledgment that some places are too special to drill, while others can be an important part of meeting our energy needs.

And in the South Park area—a vast recreational playground for the Front Range and an important source of drinking water for Denver and the Front Range—the BLM is moving ahead with a Master Leasing Plan (MLP) for the area that would identify, from the outset, both those places and natural resources that need to be protected and the best places for energy leasing to proceed.

We have said that we want federal agencies in charge of public lands to involve local and state stakeholders more closely in land management planning—that perceived disconnect has been the source of criticism and conflict in the West regarding federal oversight of public lands.

The MLP process is a new tool that promises to address some of that top-down, fragmented approach to public land management. To their credit, the BLM is listening and incorporating suggestions from local ranchers, conservation groups and elected officials into their leasing plan for South Park.

The MLP process is a new tool that promises to address some of that top-down, fragmented approach to public land management. To their credit, the BLM is listening and incorporating suggestions from local ranchers, conservation groups and elected officials into their leasing plan for South Park.

This landscape level, “smart from the start” approach is one way for stakeholders to find consensus on commonsense, balanced solutions that allow careful, responsible energy development to occur while protecting our most valuable natural resources.

The lesson I take from the Roan? We can find solutions through respectful dialogue—and we shouldn’t wait for litigation to do so. Coloradoans can meet our needs for energy development and for preserving healthy rivers and lands by talking earlier to each other and looking for common ground.

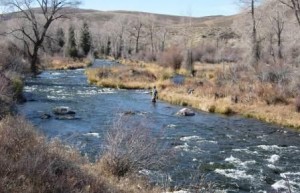

The Roan Plateau is home to outstanding big game habitat and unique native trout like those pictured here. Trout Unlimited has been hard at work on the Roan for more than two decades, with many hundreds of volunteer hours invested by the Grand Valley Anglers chapter on habitat protection and improvement projects from instream structures to riparian fencing and replanting. TU also helped install a fish barrier to protect native cutthroat trout habitat being restored by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

The Roan Plateau is home to outstanding big game habitat and unique native trout like those pictured here. Trout Unlimited has been hard at work on the Roan for more than two decades, with many hundreds of volunteer hours invested by the Grand Valley Anglers chapter on habitat protection and improvement projects from instream structures to riparian fencing and replanting. TU also helped install a fish barrier to protect native cutthroat trout habitat being restored by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The Thompson Divide (including Thompson Creek pictured here) makes up more than 220,000 acres of federal land in Pitkin, Garfield, Gunnison and Mesa counties and contains some of Colorado's most productive habitat for big game, cutthroat trout and numerous other native species. The area is used by more than 10,000 resident and nonresident big game hunters every year and serves as the headwaters to some of Colorado’s most popular fisheries including the Roaring Fork, North Fork of the Gunnison, and Crystal River.

The Thompson Divide (including Thompson Creek pictured here) makes up more than 220,000 acres of federal land in Pitkin, Garfield, Gunnison and Mesa counties and contains some of Colorado's most productive habitat for big game, cutthroat trout and numerous other native species. The area is used by more than 10,000 resident and nonresident big game hunters every year and serves as the headwaters to some of Colorado’s most popular fisheries including the Roaring Fork, North Fork of the Gunnison, and Crystal River. A small creek in southwest Wyoming just got a big upgrade. This November, a push-up style diversion was improved to a fish-friendly rock vane structure with a head-gate, reconnecting approximately 6 miles of habitat for the native Colorado River cutthroat trout that reside there. This project was unique in that it all began with the local school. Trout Unlimited partnered with the McKinnon Elementary School to study their home water, the Henry’s Fork River, through the Adopt-a-Trout program. This particular program involved tagging Colorado River cutthroat trout with telemetry tags and tracking their movement from 2014-2016. The students each got to “adopt” their own fish and follow it throughout the year. They learned a variety of river ecology lessons, including fish anatomy, macroinvertebrate identification, applying the scientific method, riparian ecosystems and many more. They also had to map where their fish moved using Google Earth.

A small creek in southwest Wyoming just got a big upgrade. This November, a push-up style diversion was improved to a fish-friendly rock vane structure with a head-gate, reconnecting approximately 6 miles of habitat for the native Colorado River cutthroat trout that reside there. This project was unique in that it all began with the local school. Trout Unlimited partnered with the McKinnon Elementary School to study their home water, the Henry’s Fork River, through the Adopt-a-Trout program. This particular program involved tagging Colorado River cutthroat trout with telemetry tags and tracking their movement from 2014-2016. The students each got to “adopt” their own fish and follow it throughout the year. They learned a variety of river ecology lessons, including fish anatomy, macroinvertebrate identification, applying the scientific method, riparian ecosystems and many more. They also had to map where their fish moved using Google Earth. Using two years of the Adopt-a-Trout data and an instream flow study that TU conducted on Beaver Creek, a major tributary, we discovered that there was a push-up dam near the confluence to the Henry’s Fork that was not allowing fish passage for a critical part of the year. None of the students’ fish were able to pass that point during the summer months. So, TU collaborated with the Lonetree Ranch to develop a fish-friendly diversion that would still allow them to receive their irrigation water, but would allow for fish passage during low flows. A head-gate was also installed so that they could turn the ditch off when they no longer needed to irrigate, leaving more water instream for the trout. Thanks to the funding provided by the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming Wildlife Natural Resource Trust and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the project was able to be completed November 2016.

Using two years of the Adopt-a-Trout data and an instream flow study that TU conducted on Beaver Creek, a major tributary, we discovered that there was a push-up dam near the confluence to the Henry’s Fork that was not allowing fish passage for a critical part of the year. None of the students’ fish were able to pass that point during the summer months. So, TU collaborated with the Lonetree Ranch to develop a fish-friendly diversion that would still allow them to receive their irrigation water, but would allow for fish passage during low flows. A head-gate was also installed so that they could turn the ditch off when they no longer needed to irrigate, leaving more water instream for the trout. Thanks to the funding provided by the Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, the Wyoming Wildlife Natural Resource Trust and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the project was able to be completed November 2016. This is just the first of many projects that will be done along Beaver Creek to benefit native trout. Over the next year, the McKinnon students will be assisting with vegetation planting and monitoring on several sections right above the diversion to provide better cover and reduce stream temperatures during the summer months. Projects like these are not only reconnecting populations of native trout, but reconnecting kids to “their” fish and river.

This is just the first of many projects that will be done along Beaver Creek to benefit native trout. Over the next year, the McKinnon students will be assisting with vegetation planting and monitoring on several sections right above the diversion to provide better cover and reduce stream temperatures during the summer months. Projects like these are not only reconnecting populations of native trout, but reconnecting kids to “their” fish and river.

The trail includes not only 3 miles of a paved multiuse trail, but features 3 bridges, 6 new formal river access points and multiple overlooks and boulder seating areas. Other improvements include two new parking lots and an expanded parking lot and restroom at Mayhem Gulch. The parking lots are a key component to bringing a new types of visitor to Clear Creek Canyon; cyclists, hikers and walkers.

The trail includes not only 3 miles of a paved multiuse trail, but features 3 bridges, 6 new formal river access points and multiple overlooks and boulder seating areas. Other improvements include two new parking lots and an expanded parking lot and restroom at Mayhem Gulch. The parking lots are a key component to bringing a new types of visitor to Clear Creek Canyon; cyclists, hikers and walkers. t was encouraging to see extended families walking the trail, leaning over the guardrail at an overlook pointing to trout rising behind a large boulder. Joggers pushing strollers paused at the overlooks on the bridges to catch their breath. Cyclists were numerous and one group took advantage of the informal boulder seating areas to stop for a picnic lunch. There were crowds of climbers at all of the popular areas, and fisherman were ducking in and out of the willows along the banks.

t was encouraging to see extended families walking the trail, leaning over the guardrail at an overlook pointing to trout rising behind a large boulder. Joggers pushing strollers paused at the overlooks on the bridges to catch their breath. Cyclists were numerous and one group took advantage of the informal boulder seating areas to stop for a picnic lunch. There were crowds of climbers at all of the popular areas, and fisherman were ducking in and out of the willows along the banks. My overall impression of the trail was extremely positive. The materials used through compliment the character of the Canyon. The improved parking areas provide additional spaces and greatly improve visitor safety and the new signage is clear and concise. The biggest improvement; however, is the trail. It allows visitors to disconnect from Highway 6 and truly immerse themselves in the Creek, the Canyon, and the Landscape.

My overall impression of the trail was extremely positive. The materials used through compliment the character of the Canyon. The improved parking areas provide additional spaces and greatly improve visitor safety and the new signage is clear and concise. The biggest improvement; however, is the trail. It allows visitors to disconnect from Highway 6 and truly immerse themselves in the Creek, the Canyon, and the Landscape. We have always prided ourselves on our ability to work in a bipartisan manner. Since Trout Unlimited was founded in Michigan in 1959, the organization has existed—and grown—through 11 different presidential administrations (29 years Republican, and 28 years Democrat). For example, several clear opportunities exist for us in the new Congress and with the new Trump Administration; these include Good Samaritan legislation to help clean up abandoned mines, a higher priority on water infrastructure improvements, and public land renewable energy legislation.

We have always prided ourselves on our ability to work in a bipartisan manner. Since Trout Unlimited was founded in Michigan in 1959, the organization has existed—and grown—through 11 different presidential administrations (29 years Republican, and 28 years Democrat). For example, several clear opportunities exist for us in the new Congress and with the new Trump Administration; these include Good Samaritan legislation to help clean up abandoned mines, a higher priority on water infrastructure improvements, and public land renewable energy legislation.

At the

At the